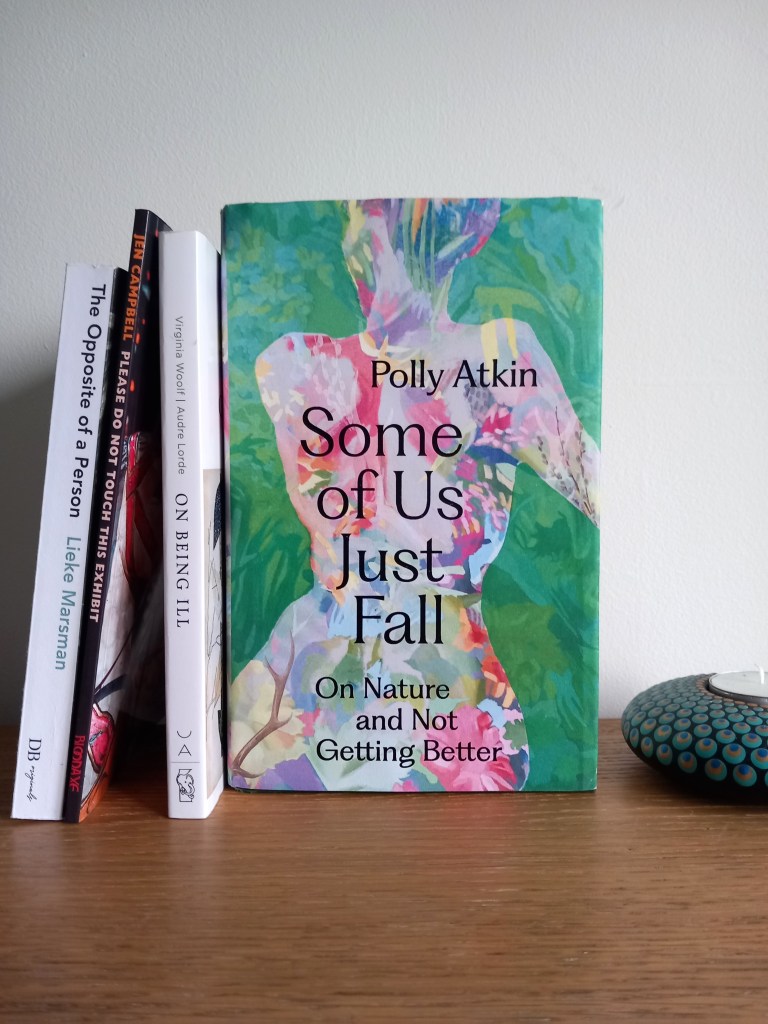

Some of Us Just Fall is a book of many things. One of the quotes on the back calls it “activism in book form” which feels right. It is also an art piece with one of my favourite covers ever and beautiful snippets of lyrical nature writing inside. It is also a nod of validation from a fellow chronically ill writer which says I believe you and these things happened, but you will find a way forward and don’t give up even when you’re staring the hypocrisy of it all in the face.

Polly Atkin has clearly taken a lot of care in the telling of her story. The title alone has several meanings. There is falling as a symptom associated with one of Atkin’s specific illnesses, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. There is the inherent randomness of who gets chronic illness. There is the trajectory for some of us that our symptoms will only get gradually worse – an antithesis to the narrative of acute illness. Atkin’s poetic background brings lines as multi-faceted as the title with breathtaking intermissions depicting the nature of Grasmere in the Lake District.

The first half of the book explores Atkin’s experience with illness before she had a name for it and the long journey to diagnosis. There are stories of missed opportunities when Atkin was a teenager, often because of doctors making sweeping generalisations about what it possibly could and could not be. There are stories of doctors not being able to accept they’re wrong. One story depicts a radiographer and a nurse not feeling able to tell the doctor they could see a break on an X-ray that the doctor had not spotted, “what I learnt from this story is that doctors can be wrong, but also that you mustn’t tell them that, not outright.”

There are stories that I won’t describe because they should be read in Atkin’s own words. Collectively, this narrative shows the sorts of doctors appointments you’ll have when you’re looking for diagnosis for the kind of illness that turns out to be chronic. The appointments where nothing happens and you feel like you’re back to square one. The appointments where the doctor admits they don’t know what to do with you but give you a step forward. The appointments where a doctor says something so outrageous, you start questioning the reality of your situation. The appointments where you ask about a potential cause and the doctor doesn’t take it well. The appointments where you ask about a potential cause and the doctor listens to you and suggest a course of action.

It takes seeing this experience as a whole to understand how doctor after doctor not taking you seriously can translate to a patient starting to question whether the pain, fatigue or other symptoms they are experiencing are real at all.

Atkin puts it like this:

“I think not just about the physical damage, but the emotional damage. The years of uncertainty and mistrust that could have been avoided. The trauma that could have been avoided. The panic I contend with every time I go into a doctor’s office. The constant fear of dismissal.”

You’re probably gathering by this point that I related to Polly Atkin’s experience a lot. Like me, she turned to writing to be able to express herself without the fear of not being believed:

“I wrote to make sense of what was happening: to weigh up what I was feeling against what I was told about what I was feeling. I would read back over it as months of confusion passed by…trying to find proof that I wasn’t creating my own illness.”

To find solidarity in these sorts of stories as someone coming to terms with chronic illness, I’ve found you have to put yourself in a really specific situation – go to a webinar, or a talk, or find specific peer support via a charity. They are the kind of stories you wouldn’t tell in passing – you need a safe space and an engaged audience. Getting these stories (the authentic ones that don’t end in someone overcoming their illness) into book form is so important. When books are accessible and available, the stories within can reach people whenever and wherever they are able to read.

Whilst in the process of seeking diagnosis for chronic illness, moments of external validity are crucial. They provide the energy to try and see a doctor again, to pursue another possible route which may lead to nowhere, or to pick yourself up after a bad experience. Atkin describes this as “the labyrinth of the body that you are trying to work your way through”.

The second half of the book explores making sense of a diagnosis and finding ways of managing the kind of illness that doesn’t go away. There is an interesting discussion on how the narrative of cure perpetuates ableist ideas.

“The dark side of cure is eradication. Cure wants to remove, to erase difference. Cure wants people like me to not be people like me.”

To elucidate this idea, Atkin explores the tragic history of the water cure, a nineteenth-century procedure now considered torture involving funnelling water down someone’s throat until the stomach fills to near-bursting, which has some roots in Grasmere. In contrast, Atkin’s scenes of nature often depict how wild swimming has helped her manage her illness when she is able to do it at her own pace.

For those managing chronic illness themselves, there are some paragraphs which explain the experience with triumphant accuracy and beautiful language.

“To pace is to quieten, to call a truce. A freedom from the disorder of the body. Temporary. We reconcile. We give permission to rest, to lay down arms, figuratively or literally.

But it is also unrest, it is also unquiet. It is peaceless movement. It is the continual effort to remember to change. To keep changing. To remain alert to the body’s disorders, to alter accordingly.”

There are so many more insights which I could reveal to you, but more than anything I’d like more readers to find the wonderment, solidarity and beauty in this book themselves. There is also a brilliant talk and Q&A with Polly Atkin on the Lighthouse Bookshop Youtube channel linked here.

If you want to read an authentic experience of chronic illness, whether to educate yourself or find solidarity, this book has it, plus an added bonus of exquisite nature writing. I will be recommending Some of Us Just Fall for years and years and have no doubt I’ll return to it for a re-read.